Demand paging in OS is a fundamental memory management technique used in modern operating systems to efficiently utilize physical memory. Instead of loading an entire program into RAM during startup, the operating system loads only the required memory pages when they are actually referenced by the CPU. This on demand loading mechanism is a core component of virtual memory systems and allows programs to run even when their total size exceeds the available physical memory.

By reducing unnecessary memory usage, demand paging improves system responsiveness, speeds up program initialization, and enhances multitasking performance. It relies on key concepts such as page tables, page faults, the Memory Management Unit (MMU), and page replacement algorithms to manage memory dynamically and efficiently.

Today, operating systems like Windows, Linux, macOS, and Android depend heavily on demand paging to balance performance, memory efficiency, and system stability. Understanding how demand paging works is essential for students, developers, and anyone studying operating systems, as it explains how modern systems handle memory-intensive applications smoothly and reliably.

What is Demand Paging in OS?

Demand paging is a memory management technique in operating systems where pages of a program are loaded into RAM only when the CPU actually needs them. Instead of loading the entire program at once, the OS waits until a page is referenced and then brings it from secondary storage into memory.

This reduces RAM usage, speeds up program startup time, and allows larger applications to run even on devices with limited physical memory. Demand paging also helps improve multitasking performance because it frees RAM for other processes.

This approach works using page tables, page faults, and virtual memory. When the CPU accesses a page that is not currently in RAM, a page fault occurs. The OS then fetches the missing page from disk, updates the page table, and resumes execution.

While demand paging improves efficiency, too many page faults can slow down the system, leading to issues like thrashing when RAM is insufficient. Overall, demand paging is essential in modern systems like Windows, Linux, macOS, and Android to handle memory efficiently and ensure smooth performance.

Why Demand Paging Is Important in Modern Operating Systems?

Demand paging plays a crucial role in how today’s operating systems, such as Windows, Linux, macOS, and Android, manage memory efficiently. Instead of loading an entire program into RAM, the OS brings in only the pages that are actually needed.

This reduces unnecessary memory usage, allows applications to launch faster, and ensures the system has enough free RAM to run multiple programs smoothly. As a result, users experience better responsiveness even on devices with limited memory.

- Loads only required pages into RAM, reducing unnecessary memory usage.

- Improves system responsiveness by allowing applications to start faster.

- Helps run multiple programs simultaneously without slowing down the system.

- Enables large applications to run even on devices with limited physical memory.

- Optimizes resource usage in virtual machines and cloud environments.

- Reduces overall RAM consumption, improving multitasking and performance.

- Prevents system overload by keeping memory usage balanced and efficient.

- Supports scalable computing in servers, virtualization, and high load systems.

How Demand Paging Works? (Step by Step Explained)

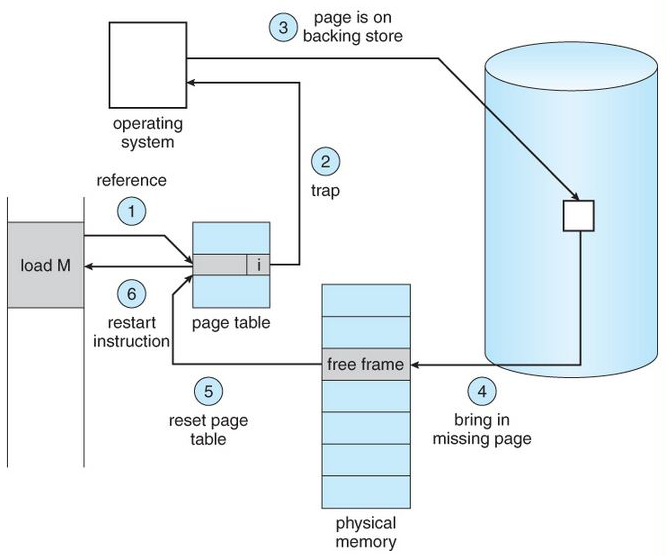

Demand paging loads a program’s memory pages from disk into RAM only when the CPU first references them; if a referenced page is not present a page fault is raised, the OS reads the page from secondary storage into a free frame, updates page tables and TLB, and then resumes the interrupted instruction.

Step by step lifecycle (exact sequence):

- CPU issues a memory reference — the processor generates a virtual address while executing instructions.

- MMU / page table lookup — the Memory Management Unit consults the process’s page table to find the mapping from virtual page → physical frame.

- Check the valid/present bit — if the page table entry (PTE) shows the page is present, compute the physical address and continue (fast path).

- Page not present → page fault trap — the MMU raises a page fault exception and transfers control to the OS kernel’s page fault handler.

- Validate the access — the OS checks whether the access is legal (within the process’ address space and respects permissions). If illegal, send a segmentation fault / terminate the process.

- Find a free frame — the OS locates a free physical frame. If none are free, it runs the page replacement algorithm (LRU, Clock, FIFO, etc.) to select a victim page to evict.

- If victim is dirty, write back — if the chosen victim page has been modified (dirty bit set), write it back to disk (swap area or backing store) before reusing the frame.

- Load the demanded page (page in) — issue I/O to read the required page from the backing store (disk/SSD) into the chosen physical frame. This is the slowest step (disk latency).

- Update page table & TLB — set the PTE’s present bit, frame number, reset reference/dirty bits as appropriate, and invalidate/update the TLB entry so the MMU uses the new mapping.

- Resume the faulting instruction — the kernel returns from the page fault handler and the CPU retries the instruction; now the memory access succeeds using the newly loaded page.

Additional important details (concise)

- TLB role: The Translation Lookaside Buffer caches recent page table entries; a TLB miss is much cheaper than a page fault, it’s a memory read to page table, not disk I/O.

- Minor vs Major page faults: Minor (soft) faults can be handled without disk I/O (e.g., page already in memory but not mapped to this process). Major (hard) faults require disk reads.

- Prefetching / clustering: OSes often read neighboring pages during a page in (anticipatory paging) to reduce future faults for sequential accesses.

- Replacement policies matter: Bad replacement choices cause thrashing (constant evict/load cycles) and huge performance loss. Monitoring working set sizes helps avoid thrashing.

- Atomicity & concurrency: The OS must handle concurrent faults and avoid race conditions when multiple threads fault on the same page, usually via page locks or by marking the PTE as “in progress.”

- Performance tradeoff: Demand paging reduces memory footprint and speeds startup, but the first access to a page pays the I/O latency cost.

Page Table and Demand Paging (Easy Explanation)

A page table is a core data structure used by the operating system to map virtual pages to physical frames in RAM. Every process has its own page table, and each entry contains details such as:

- Whether the page is currently present in RAM

- The physical frame number

- Access permissions (read/write/execute)

- Reference bit (used for replacement algorithms)

- Dirty bit (whether the page has been modified)

When the CPU accesses memory, the MMU checks the page table to determine if the required page is in RAM. If it is present, the physical address is generated instantly. If it’s not present, the OS uses demand paging to load it on the fly.

In demand paging, most page table entries are initially marked as “not present.” When the CPU references such a page, a page fault occurs. The OS then loads the required page from disk into RAM, updates the page table entry, and resumes the program. This mechanism ensures that memory is used efficiently and only the necessary pages are kept in RAM at any given time.

- Page table maps virtual pages → physical frames.

- Each process maintains its own page table.

- Demand paging relies heavily on the page table to track which pages are present or absent.

- Pages not loaded into RAM are marked as invalid / not present.

- A page fault triggers the OS to load the required page from disk.

- After loading, the OS updates the page table entry with the frame number and status.

- This helps reduce memory usage and speeds up process startup.

| Page Table Field | Meaning | Importance in Demand Paging |

|---|---|---|

| Present Bit (Valid Bit) | Indicates whether the page is in RAM | Helps detect page faults instantly |

| Frame Number | The physical frame of the page in RAM | Used to generate physical address |

| Dirty Bit | Shows if the page has been modified | Determines if page must be written back during replacement |

| Reference Bit | Shows if the page was recently used | Helps choose which page to evict |

| Access Permissions | Defines read/write/execute rules | Prevents illegal memory access |

| Swap Location | Where the page is stored on disk | Used when loading the page during a page fault |

What is a Page Fault in OS?

A page fault in an operating system occurs when a program tries to access a page that is not currently available in physical RAM. Since the page is missing, the CPU cannot continue execution and raises a page fault exception.

The OS then steps in, fetches the required page from disk or secondary storage, loads it into RAM, updates the page table, and resumes the process. Page faults are a natural part of virtual memory systems and are essential for features like demand paging.

A page fault does not always mean an error, it simply indicates that the required data isn’t in memory yet. However, frequent page faults can lead to slow performance because fetching data from disk is much slower than accessing RAM. If page faults occur excessively, the system may enter a state called thrashing, where it spends more time loading pages than executing programs.

Types of Page Faults

- Minor (Soft) Page Fault

The page is not in the process’s memory map but is already in RAM (e.g., shared memory, cached page).

No disk access needed → fast.

- Major (Hard) Page Fault

The page must be brought from disk to RAM.

Disk access needed → slow.

- Invalid Page Fault

The process accessed an illegal/invalid memory address.

Leads to segmentation fault or process termination.

Page Fault Handling

| Step | What Happens |

|---|---|

| 1. Memory Access | CPU accesses a virtual address. |

| 2. Page Table Check | MMU finds the page is not present. |

| 3. Trap to OS | Page fault exception is triggered. |

| 4. OS Validates Request | Checks if the access is legal. |

| 5. Find/Free a Frame | OS selects a free or victim frame. |

| 6. Load Page from Disk | Page is read from secondary storage (slowest step). |

| 7. Update Page Table | Mark page as present and record frame number. |

| 8. Resume Execution | CPU re-executes the interrupted instruction. |

Working Set Model in Demand Paging

The Working Set Model is a memory, management concept that helps the operating system decide which pages a process is actively using at any given moment. Instead of assuming all pages are equally important, the OS tracks the pages a process has referenced during a fixed time window called the working-

set window (Δ). All pages used within this window form the working set, the subset of memory that the process needs to run smoothly without frequent page faults.

In demand paging, the working set model is crucial because it helps the OS determine how many pages to keep in RAM for each process. If the working set fits in physical memory, the process runs efficiently. But if the working set is larger than available RAM, the system begins generating excessive page faults, eventually leading to thrashing. By monitoring each process’s working set, the OS ensures stable performance, prevents unnecessary page replacements, and maintains overall system responsiveness.

- The working set is the set of recently used pages by a process.

- Defined using a time window Δ (e.g., last 10ms or 100ms of memory references).

- Helps the OS understand how much memory a process actually needs.

- If the working set fits in RAM → fewer page faults → smooth execution.

- If it doesn’t fit → page faults increase → leads to thrashing.

- OS allocates memory based on the working set to maintain system stability.

- Allows fair and efficient distribution of RAM among processes.

| Concept | Explanation | Importance in Demand Paging |

|---|---|---|

| Working Set (WS) | Set of pages actively used by a process within time window Δ | Helps determine required memory for smooth execution |

| Δ (Working Set Window) | Time duration to measure page references | Defines which pages are considered “active” |

| WS Size | Number of pages in the working set | OS uses it to allocate or reclaim memory |

| Frequent Page Faults | Occur when WS doesn’t fit in RAM | Indicates memory pressure or thrashing |

| Thrashing | System spends more time loading pages than executing processes | Working Set Model helps detect and prevent it |

| Memory Allocation | OS allocates RAM based on WS size for each process | Ensures balanced and efficient paging |

Page Replacement Algorithms Used in Demand Paging

In demand paging in OS, the operating system loads pages into RAM only when they are needed. But since physical memory is limited, the OS must often replace an existing page to make space for a new one. This decision is handled using page replacement algorithms, which determine which page should be removed to minimize page faults and keep the system running efficiently. A good replacement algorithm helps maintain high performance, while a poor one can lead to excessive page faults and even thrashing.

These algorithms use different strategies — such as the age of a page, how frequently it is used, or future predictions, to make intelligent decisions. Modern OSes rely on a combination of these algorithms to achieve the best balance between speed, memory efficiency, and system stability.

Key Page Replacement Algorithms

1. FIFO (First-In, First-Out)

- Replaces the oldest loaded page in memory.

- Simple but may remove frequently used pages.

- Can suffer from Belady’s Anomaly.

2. LRU (Least Recently Used)

- Replaces the page that hasn’t been used for the longest time.

- Very effective and commonly used.

- Requires hardware support or additional tracking.

3. Optimal Page Replacement (OPT)

- Replaces the page that will not be used for the longest time in the future.

- Theoretically best but impossible to implement perfectly in real systems.

- Used for benchmarking.

4. LFU (Least Frequently Used)

- Removes the page with the lowest access frequency.

- Useful when frequently used pages must stay in RAM.

- May suffer when older pages accumulate high counts.

5. Clock / Second Chance Algorithm

- A practical improvement of FIFO.

- Uses a circular buffer (clock hand) with a reference bit to give pages a second chance.

- Efficient and widely used in real OSes.

| Algorithm | How It Works | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIFO | Removes oldest loaded page | Simple, fast | Can remove important pages; Belady’s anomaly |

| LRU | Removes least recently used page | Accurate & effective | Requires hardware/extra tracking |

| Optimal (OPT) | Removes page unused for the longest future time | Lowest page faults | Not implementable in reality |

| LFU | Removes least frequently used page | Keeps frequently used pages | Old pages may get unfair protection |

| Clock / Second Chance | Uses a circular pointer + reference bit | Efficient, balances accuracy & speed | Slightly complex implementation |

Thrashing in OS (Major Problem of Demand Paging)

Thrashing is a severe performance problem in operating systems that happens when the system spends more time swapping pages in and out of memory than executing actual processes. This occurs when the working set of a process (the pages it actively needs) is larger than the available RAM. As a result, the CPU continuously triggers page faults, forcing the OS to load pages from disk repeatedly, causing the system to slow down dramatically.

In demand paging, thrashing is the biggest risk because pages are loaded only when needed. If too many processes compete for limited memory, page faults increase rapidly, and the OS becomes overloaded with paging operations. Instead of executing instructions, the CPU stays busy handling page faults, leading to extremely poor system performance, freezing, lag, or near, total unresponsiveness. Preventing thrashing is critical to maintaining system stability and efficiency.

| Cause | Explanation | Why It Leads to Thrashing |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient RAM | Not enough memory to hold active working sets | Forces constant page replacements |

| Too Many Active Processes | High multitasking load | Working sets overlap and exceed available RAM |

| Large Working Sets | Programs needing more memory than usual | Increases major page faults |

| Poor Page Replacement Algorithms | Frequent removal of useful pages | Causes repeated reloading of the same pages |

| High Multiprogramming Level | Too many programs competing for frames | Memory pressure rises rapidly |

Advantages & DisAdvantages of Demand Paging in OS

| Advantages of Demand Paging | Explanation | Disadvantages of Demand Paging | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficient Memory Usage | Loads only required pages, saving RAM | Page Fault Overhead | Disk access during page faults slows execution |

| Faster Program Startup | Programs open quickly since not all pages load at once | Risk of Thrashing | Too many page faults can freeze or slow the system |

| Supports Large Applications | Allows apps larger than physical RAM to run | Slower First Time Access | First access to a page is slow due to disk loading |

| Better Multitasking | More processes fit in RAM simultaneously | Higher Disk Dependency | Heavy reliance on disk can reduce performance |

| Reduces Initial I/O Load | Only essential pages trigger disk reads | Complex OS Design | Requires MMU, TLB, and advanced algorithms |

Real Life Example of Demand Paging

A simple real life example of demand paging happens when you open a large application like Microsoft Word, Google Chrome, or Photoshop. When you launch these apps, the operating system does not load the entire program into RAM. Instead, it loads only the essential pages required to start the interface.

As you begin typing, opening menus, or using advanced tools, the OS loads additional pages only when you access those features. This means features like spell check, insert menu, templates, or extensions are loaded on demand, not upfront.

This on demand loading gives you a fast startup experience while keeping RAM usage low. If a feature hasn’t been used, its pages remain on disk and do not consume memory. But the first time you use a new feature, the OS may momentarily pause to fetch the required page, this is demand paging in action.

Demand Paging vs Pre-Paging (Quick Comparison)

Demand Paging loads a page only when the CPU first tries to access it, which means it reacts to page faults as they occur. This reduces initial memory usage but can slow down performance due to frequent page faults, especially when many pages are needed in a short time.

Pre-Paging, on the other hand, loads a group of pages before they are actually needed, based on the assumption that nearby pages will be used soon. This reduces the number of page faults and speeds up execution, but it may waste memory by loading pages that may never be used.

| Feature | Demand Paging | Pre-Paging |

|---|---|---|

| Loading Style | Loads pages when accessed | Loads pages in advance |

| Initial Page Faults | High | Low |

| Memory Usage | Efficient (no extra pages) | May waste memory |

| Performance | Slower on first access | Faster startup & smoother execution |

| Predictability Needed? | No | Yes (works best with predictable access patterns) |

| Suitable For | Low RAM devices, general OS use | High-performance systems, predictable workloads |

| Risk of Thrashing | Higher if many faults occur | Lower due to fewer initial faults |

Conclusion

Demand paging is a fundamental memory management technique that allows modern operating systems to load only the necessary pages into RAM, improving performance, reducing memory waste, and enabling large applications to run smoothly even on devices with limited resources. B

y loading pages on demand, the system starts programs faster, handles multitasking more efficiently, and uses physical memory more intelligently. However, demand paging also comes with challenges, such as page fault overhead, disk dependency, and the risk of thrashing when memory pressure is high.

This is why concepts like the working set model, page replacement algorithms, and pre-paging play an essential role in maintaining system stability. Overall, understanding demand paging helps users, developers, and students appreciate how operating systems balance speed, memory, and efficiency to deliver smooth, reliable performance across all types of applications.